I would like to invite you to journey with St Paul as he explores the theme of the universal call to holiness. For St. Paul, this journey begins on the road to Damascus which St. Luke narrates in Acts 9. Prior to his conversion, Saul is a pious Pharisee. He was probably from the School of Shammai which believed that Israel must be free of the gentile yoke. He tells us in Acts 22; “I am a Jew, born at Tarsus in Cilicia, but brought up in this city at the feet of Gamaliel, educated according to the strict manner of the law of our fathers, being zealous for God as you all are this day” (Acts 22:3). As a zealous Pharisee, he had gone “to the high priest and asked him for letters to the synagogues at Damascus, so that if he found any belonging to the Way, men or women, he might bring them bound to Jerusalem” (Acts 9:1-2). Saul is feeling very righteous as travels to Damascus, so when he experiences “a light from heaven [that] flashed about him” (Acts 9:3) he is expecting a heavenly cheer. He expects to hear, “well done my good and faithful servant.” Saul may have been thinking of the stories from other Rabbinic mystics who had seen visions of the Merkabah or throne of God descending from heaven as the prophet Ezekiel experienced in the Old Testament. Instead what he hears shocked him. He feel to the ground, began to dialogue with a heavenly voice. The voices cries out, “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?” To which Saul replies with some confusion, “Who are you, Lord?” And the heavenly voice replies, “I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting; but rise and enter the city, and you will be told what you are to do” (Acts 9:5-6).

We need to think about this, the heavenly voice said, “I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting…” We need to ask, did the Rabbi Saul ever literally persecute Jesus? Had he even met Jesus? As far as we can tell the answer is “No.” He had persecuted Christians, or the followers of the way as they are called in this passage. Here for the first time he learns the central truth about communion in Christ. To persecute the Church is to persecute Jesus. Jesus and the Church are one. After this life changing encounter, Saul the Rabbi becomes Paul the Apostle of Christ Jesus, by the will of God (1 Corinthians 1:1).

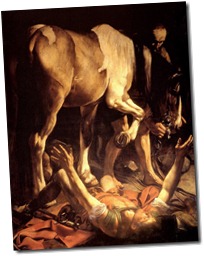

I would like to note a small pet peeve about this passage. In Catholic art since the middle ages, St. Paul is always depicted as falling off a horse in this episode. If you search the text carefully you will not find a horse. What you do find, however, is that after St. Paul was blinded the men he was with “led him by the hand and brought him into Damascus” (Acts 9:8). If you have a blind man and a horse, would you lead him by the hand, or put him on the horse and lead the horse instead?

Returning to our main point, St. Paul learns that to persecute the Church is to persecute Jesus. Jesus and the Church are one. From this experience the Apostle Paul gains one of his most characteristic ways of describing all of the faithful as “in Christ Jesus.” The expression “in Christ” or “in Christ Jesus” occurs 164 times in the Pauline corpus. Furthermore, if you investigate this theme, to be “in Christ” is to be “in the Spirit.”

Writing to the Galatians St Paul, notes,

“But now that faith has come, we are no longer under a custodian; 26for in Christ Jesus you are all sons of God, through faith. 27For as many of you as were baptized into Christ have put on Christ” (Galatians 3:26-27)

By virtue of our baptism we have been joined to Christ.. This oneness includes bearing his image, being holy as he is holy. This is the inescapable vocation of all the faithful.

SGM