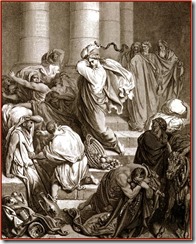

In today’s Gospel reading Jesus challenges the great crowds that are following him to take stock of the cost of his discipleship. Jesus says, “If anyone comes to me without hating his father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters, and even his own life, he cannot be my disciple” (Luke 14:26). Jesus is not literally telling us to hate our families but warning us that Jesus must be our first love. If there is a conflict between loving Christ and respecting or honoring our family, the cost of discipleship is to renounce our family for the sake of the kingdom. Jesus continues, “Whoever does not carry his own cross and come after me cannot be my disciple” (Luke 14:27). Being a disciple comes with a cost. We must be willing to suffer. Notice the two aspects of discipleship highlighted in these verses. Jesus says. “If anyone comes to me. . .” and then in the next verse he says, “come after me.” Our faith is both a beginning and an ongoing journey. Our modern culture, which is perhaps influenced by certain types of Protestantism, tends to focus only on the initial decision or the ‘altar call.’ If the focus is only on the beginning, then we will fail to grow and continue the work of conversion than God has started in our heart.

During the Nazi occupation of Germany, the German Lutheran pastor, Dietrich Bonhoeffer complained against those who professed faith in Christ but allowed the Nazis to control the German State Church and to commit atrocities against the Jews. He helped found a dissident free ‘Confessing Church’ and eventually was executed in a concentration camp for his views. Bonhoeffer believed that our faith should impact the Christian’s role in the secular world. He called the separation of faith and living, “cheap grace.” In 1937 Bonhoeffer wrote, “Cheap grace is the mortal enemy of our church. Our struggle today is for costly grace” (The Cost of Discipleship). Have we committed ourselves to intentionally following Jesus?

The Fathers of the Second Vatican Council noted a similar problem at the time of the council. They complain about the error of those, “who imagine they can plunge themselves into earthly affairs in such a way as to imply that these are altogether divorced from the religious life. This split between the faith which many profess and their daily lives deserves to be counted among the more serious errors of our age” (GS 43).

In this Sunday’s Gospel, Jesus is calling us to live one unified life in him. We must not have a separate family, political or business life and a private religious life. We must follow after him completely even if it is a costly call of discipleship. Jesus gives two illustrations on counting this cost and then he concludes, “In the same way, anyone of you who does not renounce all his possessions cannot be my disciple.”

Once again this is not a call to hate our family, or to despise the world and all earthly possessions. The cost of discipleship is a daily endeavor, it means keeping Jesus at the center of our world. One traditional practice for this spiritual accounting is the examination of conscience. St. Ignatius of Loyola proposed a method involving five simple steps. First, begin by making an act of thanksgiving (Luke 17:15-16a). Next, pray and ask God for the grace to know ourselves and to have the courage to correct our faults. Thirdly, take a few minutes to review the hours of our day noting our faults in thought, word, deeds and omissions. Fourth, pray and ask God’s pardon for our sins. Finally make a resolution to improve ourselves in some small point of struggle during the next day (Spiritual Exercises, 43).