This series of posts will follow St. Augustine’s own story of his life in his most famous work, Confessions. Augustine will describe his infancy, childhood, adolescence, youth[i] as well as his conversation and early life as a Christian. As we read Confessions we will examine each stage of his life in some detail but as an initial framework we should note some significant turning points in his life which divide his life into four periods. His life is divided into four periods by three ‘sign posts.’ [ii] The period of his early life, his conversion and Baptism (386), his ordination to the priesthood (391) and subsequently to the episcopacy, and the period following his re-examination of Paul’s letter to the Romans and his reply to Simplicianus (396). At each of these points his thinking takes a significant shift.

Augustine’s Early Life

Apparently the general atmosphere of the home was Christian it was not initially very pious. Although St. Augustine recounts that he first learned his faith from his earliest memories. “with my mother’s milk”. . . “my tender little heart had drunk in that name.” (Conf. III.4.8) Following a misguided practice of the times, young Augustine was enrolled by his parents in the catechumenate but not baptized. He notes; “My cleansing was therefore deferred on the pretext that if I lived I would inevitably soil myself again, for it was held that the guilt of sinful defilement incurred after the laver of baptism was graver and more perilous” (Conf., I, 11.17)[iv]. He laments this practice, and what he regards as the squandering of his youth. He notes that in his youth he initially turned his “attention to the Holy Scriptures to find out what they were like” (Conf. III.5.9). Unfortunately, after comparing the Bible to Cicero’s dignified Latin prose he judged the Scriptures to be ‘unworthy’ (Conf. III.5.9) He later notes,

“My swollen pride recoiled from its style and my intelligence failed to penetrate to its inner meaning. Scripture is a reality that grows along with little children, but I distained to be a little child and in high and mighty arrogance regarded myself as grown up.” (Conf. III.5.9)

Joseph T. Lienhard, S.J. comments on the difference between the Latin Bible Augustine read and the later Vulgate translation;

“The Latin Bible that Augustine read was different. Its language was uncultivated, awkward, grammatically deficient, sometimes barbarous, and occasionally incomprehensible. A man trained to exquisite good taste, who sneered at those who said omo instead of homo, (Confessions 1, 18, 29) might well find the Christian Bible repulsive.”[v]

The main concern of his parents was for his career and so he was sent to the metropolis of Carthage to study rhetoric. His studies of Cicero lead him to an interest in philosophy. In his personal life he entered an unofficial marriage with a concubine and had a son, Adeodatus.

Augustine the Manichean

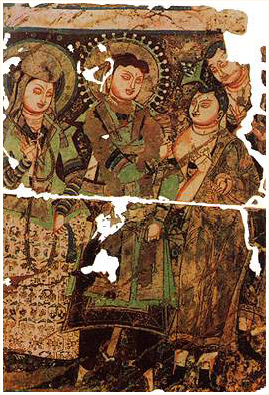

While in Carthage, he joined a self styled ‘Christian’ group following the Mesopotamian prophet Mani. He became an ‘auditor’ (listener or hearer) of the Manicheans. Manichaeism answered the question of the existence of evil by proposing a radical dualism between the realm of light, or God and the realm of darkness or Satan. Adam was the product of the mating of a male and female demon, as was Eve. The first human parents are not the creation of God but resulted from evil’s initiative. Light was trapped in the visible world. God counters this tactic by sending Jesus from the light realm to reveal divine knowledge (gnosis) to Adam and Eve. For the Manicheans Jesus was not the same as the orthodox Christianity, since human flesh in their view has evil origins and comes about through procreation which emulates the demonic origin of Adam and Eve[vi].

While in Carthage, he joined a self styled ‘Christian’ group following the Mesopotamian prophet Mani. He became an ‘auditor’ (listener or hearer) of the Manicheans. Manichaeism answered the question of the existence of evil by proposing a radical dualism between the realm of light, or God and the realm of darkness or Satan. Adam was the product of the mating of a male and female demon, as was Eve. The first human parents are not the creation of God but resulted from evil’s initiative. Light was trapped in the visible world. God counters this tactic by sending Jesus from the light realm to reveal divine knowledge (gnosis) to Adam and Eve. For the Manicheans Jesus was not the same as the orthodox Christianity, since human flesh in their view has evil origins and comes about through procreation which emulates the demonic origin of Adam and Eve[vi].

Augustine’s conversion takes place after he succeeds to the Chair of Rhetoric in Milan in 383. Here he meets Bishop Ambrose who is an eloquent speaker and who defends the Old Testament against the criticisms of Manicheans. St. Augustine’s main difficulty with the Bible (aside from the poor Latin style of his translation) was the lack of agreement between the genealogies of Christ in Gospels of Matthew and Luke. Looking back he writes;

“I am speaking to you as one who was myself caught out once upon a time, when as a lad I wanted to tackle the divine Scriptures with techniques of clever disputation before bringing to them the spirit of earnest inquiry. In this way I was shutting the door of my Lord against myself by my misplaced attitude; I should have been knocking at it for it to be opened, but instead I was adding my weight to keep it shut.”[vii]

Again looking back in his work The Usefulness of Belief (AD 391), Augustine writes,

“But there is nothing more rash—and rashness as a boy I had plenty—than to desert the professed expositors of books which they possess and hand on to their disciples, and instead to go asking the opinion of others who, for no reason I can think of, have declared most bitter war against the authors of these books.”[viii]

Under the teaching of the Manicheans Augustine had come to profess “despair” which led him to believe that the Old Testament was filled with difficulties that could not be resolved (Conf. V.14.24).

Text © Scott McKellar 2011

[i] St Augustine follows the ages of man according to the ancient world: infantia, puerita, adulescens, and iuventus. Frederick Van Fleteren, “Confessions” in Augustine through the Ages: An Encyclopedia, ed. Allan D. Fitzgerald, O.S.A., Grand Rapids, Erdmanns, 1999, p. 229. James J. O’Donnell notes, “To approach that book with the best effect, let us dwell on the Augustine of 397, the forty-two-year-old getting ready to tell his story in the form destined to become famous. For him, “youth” (iuventus) ended at forty-five, to be succeeded by “maturity” (gravitas) and then by “old age” (senectus) at sixty.” O’Donnell, Augustine: A New Biography (New York: Harper 2005) p. 26-27.

[ii] John M. Rist, Augustine, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994. p. 14.

[iii] Peter Brown, Augustine of Hippo: A Biography, Revised Edition with a New Epilogue, ?

[iv] Unless otherwise noted all quotations from, St. Augustine, Confessions, trans. Maria Boulding, O.S.B., The Works of Saint Augustine for the 21st Century, Ed John Rotelle, O.S.A., New York, New City Press, 1997.

[v]Joseph T. Lienhard , Augustinian Studies Volume 27, Issue 1 – 1996, p. 9).

[vi] J. Kevin Coyle, “Mani, Manicheism,” in Augustine through the Ages: An Encyclopedia, ed. Allan D. Fitzgerald, O.S.A., Grand Rapids, Eerdmans, 1999, esp. 521-522, cf. Serge Lancel, St. Augustine, trans. Antonia Nevill, London, SCM Press, 2002, p. 31-36.

[vii] St. Augustine, Sermon 51, trans. Edmund Hill, O.P., The Works of Saint Augustine for the 21st Century, Ed. John Rotelle, O.S.A., New York, New City Press, 1997, 51.6.

[viii] St Augustine, De utilitate credendi , vi, 13, trans. Burleigh, p. 301.

No comments:

Post a Comment