Historian Serege Lancel notes that “the spiritual and emotional chronology of the Confessions . . . does not always match up with the calendar reconstructed by historians.”[ii] Bishop Ambrose bursts into the narrative of Confessions as a central figure. Clearly the focus is one Augustine’s enlightenment and not on the Bishop of Milan per se. Ambrose did not begin his career in the Church. He was a student of law and had worked his way up the ranks of government office to become the governor of the province of Milan. Lancel says he had “the promise of one of the most brilliant career of the century” in the imperial court. What prompted him to become a bishop?

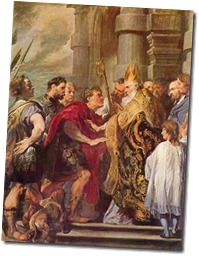

One the death of bishop Auxentius, in 373, the situation in the town [of Milan] was critical; the dead prelate was of Arian faith, thus the representative of a minority that was important but on decline in the face of Catholic dominance in the city. A turbulent mob burst into the basilica where the bishops of the province held their meeting, assembled to ordain a successor to Auxentius, and both factions put pressure on an electoral body which was itself divided and irresolute. The rising had to be put down and order re-established. Rather than bring in the troops, the governor of the province chose to intervene in person; he entered the church, obtained silence, began to speak and made the people listen when he appealed for calm. The crowd then acclaimed him and in one voice demanded this unanimously respected governor for their bishop—a governor who was none other than Ambrose.[iii]

Although Ambrose was certainly a faithful Christian catechumen, he was baptized after his accession to the episcopacy and “was less familiar with the Scriptures than with Cicero and Virgil.”[iv] Ambrose took his charge very seriously and was forced to learn and teach simultaneously. He had the good fortune of excellent knowledge of both Greek and Latin, so he was able to read the Greek Fathers, especially the “Cappadocians,” Basil of Caesarea and Gregory of Nazianzius, as well as Origen and even the Jewish exegete Philo of Alexandria. From these Fathers he learned the allegorical method of interpreting the Old Testament.

Augustine met Bishop Ambrose in 385, more than ten years after he became bishop. As Augustine listened to Bishop Ambrose preach, he was convinced by the spiritual interpretation of the Old Testament that his former Manichaean objections about the Old Testament are unfounded and that what the Church says about physical and spiritual realities made perfect sense. Augustine notes, “I now began to prefer Catholic doctrine” (6.5.7). He also began to realize that many things he believed in ordinary life were accepted on the basis of authority, or on the “testimony of friends, or physicians, or various people” (6.5.7). Even the fact that he was born of a particular set of parents could not be known apart from the testimony of others. The pure philosophy of the Academics had not been able to reveal this to him. “It was because we were weak (Romans 5:6) and unable to find the truth by pure reason that we needed the authority of the sacred scriptures; and so I began to see that you would not have endowed them with such authority among all nations unless you had willed human beings to believe in you and seek you through them” (6.5.8). Augustine comments on the ability of sacred scripture to be accessible to all people, and yet to contain profound mysteries (Latin: sacramentum). He notes;

The authority of the sacred writings seemed to me all the more deserving of reverence and divine faith in that scripture was easily accessible to every reader, while guarding a mysterious dignity in its deeper sense (6.5.8).

Augustine was still mired in his journey forward by his seeking happiness in such empty pursuits as worldly “honors, wealth, and marriage” (6.6.9). This appears to be pointing to the vices of 1 John 2:16 “the desire of the flesh, and the desire of the eyes, and the arrogance of a life”[v] This comment by Augustine leads into an anecdote. He recalls that once while walking in Milan he passed a poor drunken beggar. The man was undeniably happy and filled with joy—not true joy of course. This leads him to reflect on his own unhappiness and the worldly false hopes he has just named. He reflects on this with his friends, Alypius and Nebridius which leads to a small digression on each of his friends.

Text © Scott McKellar 2011

All quotes in this series of blogs from Confessions are from, St. Augustine, Confessions, trans. Maria Boulding, O.S.B., The Works of Saint Augustine for the 21st Century, Ed John Rotelle, O.S.A., (New York, New City Press, 1997)

[i] Peter Brown, Augustine, p. 69-78; Neil McLynn, “Ambrose of Milan,” in Augustine through the Ages: An Encyclopedia, ed. Allan D. Fitzgerald, O.S.A., Grand Rapids, Eerdmans, 1999, p. 17-19. Lancel, St. Augustine, p. 65-77.

[ii] Ibid., p. 67.

[iii] Ibid., p. 67-68.

[iv] Ibid., p. 68-69.

[v] concupiscentia carnis est, et concupiscentia oculorum, et superbia vitæ.

No comments:

Post a Comment