The first part of the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy focuses on the meaning and beauty of the liturgy (SC 1-13), and the active participation of the faithful in the liturgy (SC 14-20). The remainder of the constitution focuses on specific reforms. In regard to these reforms, the Council Fathers note;

There must be no innovations unless the good of the Church genuinely and certainly requires them; and care must be taken that any new forms adopted should in some way grow organically from forms already existing (SC 23).

I would like to focus here on the reforms which relate to the use of sacred art in worship. The Book of Revelation which completes the text of the New Testament ends with a curious passage regarding the new heavenly Jerusalem of eternity. Speaking of the heavenly city, St. John writes;

The nations will walk by its light, and to it the kings of the earth will bring their treasure. During the day its gates will never be shut, and there will be no night there. The treasure and wealth of the nations will be brought there, but nothing unclean will enter it . . . (Revelation 21:24-27)

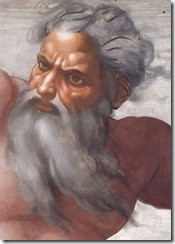

Most of us have never considered that some aspect of human culture or some human artifact might have eternal significance. To be counted in this category it would have to be some holy and pure ‘art’ which reflects the infinite beauty of God. Philosophers have viewed goodness, truth and beauty as three self-evident and interconnected qualities in our world. Theologians have seen these qualities as a reflection of God’s own perfections. God himself is the “original source of beauty.” (Wisdom 13:3). The Swiss theologian Hans Urs Von Balthasar complained that our modern world has tried to quietly jettison ‘beauty’ from this list. He warns that in a world where we can no longer see or reckon with beauty, “the good also loses its attractiveness” and “the self-evidence of why it must be carried out” is also damaged (Glory of the Lord, I:19).

The Council Fathers note in the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy that the fine arts are among the noblest human activities because their purpose is an attempt to portray by the work of human hands the infinite beauty of God (SC 122). They distinguish between religious art and sacred art which is much like the distinction between a poem and a prayer. The ‘sacred arts’ involve the “sacred imitation of God the Creator, and are concerned with works destined to be used in Catholic worship, to edify the faithful, and to foster their piety and their religious formation (SC 127).”

The Fathers note that at a diocesan level there are three separate areas of concern which are all interrelated; the sacred liturgy, sacred music and sacred art. The Council Fathers suggest that these areas of concern require thoughtful and coordinated leadership (SC 46). Today perhaps the most neglected and misunderstood aspect of worship is that of sacred art (SC 122-130).

The Fathers urge that we favor and encourage art “which is truly sacred” and which strives “after noble beauty rather than mere sumptuous display” (SC 124). Earlier, in reference to the rites of the liturgy, the Fathers used the expression “noble simplicity” (SC 34). This could lead someone to conclude that the Fathers of the council were advocating a minimalist or even anti-art stance. The idea that “noble simplicity” justifies a kind of Calvinist stripping of the altars and removing the statues and art, would be a clear misunderstanding. The expression “noble simplicity” is a catch phrase coined by the German archaeologist and art critic Johann Joachim Wincklemann (1717-1768). The expression in this context refers to Wincklemann’s observations about the elements of form and beauty found in classical Greek sculpture. Wincklemann inspired the Neo-classical movement in art which imitated the forms of classical Greek statuary. Noble simplicity would imply the use of the perfection of human beauty and “sedate grandeur in gesture and expression” which reveal the greatness of the soul beneath the passion of the figures.

Tempering such an understanding of art the Fathers note;

“The Church has not adopted any particular style of art as her very own; she has admitted styles from every period according to the natural talents and circumstances of peoples, and the needs of the various rites” (SC 123).

At the same time they also caution against a completely undisciplined and unprincipled notion of art,

“Let bishops carefully remove from the house of God and from other sacred places those works of artists which are repugnant to faith, morals, and Christian piety, and which offend true religious sense either by depraved forms or by lack of artistic worth, mediocrity and pretense” (SC 124).

The Fathers advocate a moderate and thoughtful use of sacred images (SC 125) and even the consultation of art experts (SC 126). Sacred art should have organic connection to the forms already existing in sacred tradition (SC 23), reveal the “infinite beauty of God” (SC 122) “edify the faithful”, and “foster their piety and their religious formation” (SC 127). As mentioned above, sacred art needs to join with the sacred liturgy and sacred music in “redounding to God’s praise and glory” with the “aim of turning men’s minds devoutly toward God” (SC 122). Sacred art is never merely art for art’s sake, but art in the service of the human soul as it contemplates the beauty of God.

No comments:

Post a Comment